In a previous blog post Why NFSv4.1 and pNFS are Better than NFSv3 Could Ever Be, some of the issues with NFSv3 that made it difficult to implement as a WAN based or data center wide protocol were discussed. The question then becomes; why not move to NFSv4 instead of NFSv4.1? Isn’t that a bigger leap from NFSv3?

Well, practical experience and some issues with NFSv4 made NFSv4.1 a necessity; for one, it introduces the key concept of sessions, and provides a foundation for pNFS (parallel NFS) which we’ll discuss in a later blog post. And all the features of NFSv4 were carried over into NFSv4.1, since it was a minor version update; there’s little more to do to take advantage of NFSv4.1, so that’s where your focus evaluation and implementation should be.

TCP for Transport

NFSv3 supports both TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and UDP (User Datagram Protocol), and UDP is sometimes employed (for those applications that support it) because it is perceived to be lightweight and faster in comparison to TCP.

The downside of UDP is that it’s connectionless (that is, stateless) and an unreliable protocol. There is no guarantee that the datagrams will be delivered in any given order to the destination host — or even delivered at all — so applications must be specifically designed to handle missing, duplicate or incorrectly ordered data. UDP is also not a good network citizen; there is no concept of congestion or flow control, and no ability to apply quality of service (QoS) criteria.

The NFSv4 specification requires that any transport used provides congestion control. The easiest way to do this is via TCP. By using TCP, NFSv4 clients and servers are able to adapt to known frequent spikes in unreliability on the Internet; and retransmission is managed in the transport layer instead of in the application layer, greatly simplifying applications and their management on a shared network.

NFSv4 also introduces strict rules about retries over TCP in contrast to the complete lack of rules in NFSv3 for retries over TCP. As a result, if NFSv3 clients have timeouts that are too short, NFSv3 servers may drop requests. NFSv4 uses the timers that are built into the connection-oriented transport.

Network Ports

To access an NFS server, an NFSv3 client must contact the server’s portmapper to find the port of the mountd server. It then contacts the mount server to get an initial file handle, and again contacts the portmapper to get the port of the NFS server. Finally, the client can access the NFS server.

This creates problems for using NFS through firewalls, because firewalls typically filter traffic based on well-known port numbers. If the client is inside a firewalled network, and the server is outside the network, the firewall needs to know what ports the portmapper, mountd and nfsd servers are listening on. The mount server can listen on any port, so telling the firewall what port to permit is not practical. While the NFS server usually listens on port 2049, sometimes it does not. While the portmapper always listens on the same port (111), many firewall administrators, out of excessive caution, block requests to port 111 from inside the firewalled network to servers outside the network. As a result, NFSv3 is not practical to use through firewalls. (Aside from which, without security, it’s risky too.)

NFSv4 uses a single port number by mandating the server will listen on port 2049. There are no “auxiliary” protocols like statd, lockd and mountd required as the mounting and locking protocols have been incorporated into the NFSv4 protocol. This means that NFSv4 clients do not need to contact the portmapper, and do not need to access services on floating ports.

As NFSv4 uses a single TCP connection with a well-defined destination TCP port, it traverses firewalls and network address translation (NAT) devices with ease, and makes firewall configuration as simple as configuration for HTTP servers.

Mounts and Automounter

The automounter daemons and the utilities on different flavors of UNIX and Linux are capable of identifying different NFS versions. However, using the automounter will require at least port 111 to be permitted through any firewall between server and client, as it uses the portmapper.

This is undesirable if you are extending the use of NFSv4 beyond traditional NFSv3 environments, so in preference the widely available “mirror mount” facility can be used. It enhances the behavior of the NFSv4 client by creating a new mountpoint whenever it detects that a directory’s fsid differs from that of its parent and automatically mounts filesystems when they are encountered at the NFSv4 server .

This enhancement does not require the use of the automounter and therefore does not rely on the content or propagation of automounter maps, the availability of NFSv3 services such as mountd, or opening firewall ports beyond the single port 2049 required for NFSv4.

Internationalization Support; UTF-8

Yes, those funny characters outside of US-ASCII are supported. In a welcome recognition that it set no longer provides the descriptive capabilities demanded by languages with larger alphabets or those that use an extensive range of non-Roman glyphs, NFSv4 uses UTF-8 for file names, directories, symlinks and user and group identifiers. As UTF-8 is backwards compatible with 7 bit encoded ASCII, any names that are 7 bit ASCII will continue to work.

Compound RPCs

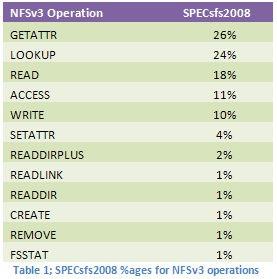

Latency in a wide area network (WAN) is a perennial issue, and is very often measured in tenths of a second to seconds. NFS uses Remote Procedure Calls (RPCs) to undertake all its communication with the server, and although the payload is normally small, meta-data operations are largely synchronous and serialized. Operations such as file lookup (LOOKUP), the fetching of attributes (GETATTR) and so on, make up the largest percentage by count of the average traffic load on NFS.

This mix of a typical NFS set of RPC calls in versions prior to NFSv4 requires each RPC call is a separate transaction over the wire. NFSv4 avoids the expense of single RPC requests and the attendant latency issues and allows these calls to be bundled together. For instance, a lookup, open, read and close can be sent once over the wire, and the server can execute the entire compound call as a single entity. The effect is to reduce latency considerably for multiple operations.

Delegations

Servers are employing ever more quantities of RAM and flash technologies, and very large caches in the orders of terabytes are not uncommon. Applications running over NFSv3 can’t take advantage of these caches unless they have specific application support. With increasing WAN latencies doing every IO over the wire introduces significant delay.

NFSv4 allows the server to delegate certain responsibilities to the client, a feature that allows caching locally where the data is being accessed. Once delegated, the client can act on the file locally with the guarantee that no other client has a conflicting need for the file; it allows the application to have locking, reading and writing requests serviced on the application server without any further communication with the NFS server. To prevent deadlocking conditions, the server can recall the delegation via an asynchronous callback to the client should there be a conflicting request for access to the file from a different client.

Migration, Replicas and Referrals

For broader use within a datacenter, and in support of high availability applications such as databases and virtual environments, copying data for backup and disaster recovery purposes, or the ability to migrate it to provide VM location independence are essential. NFSv4 provides facilities for both transparent replication and migration of data, and the client is responsible for ensuring that the application is unaware of these activities. An NFSv4 referral allows servers to redirect clients from this server’s namespace to another server; it allows the building of a global namespace while maintaining the data on discrete and separate servers.

Sessions

Perhaps one of the most significant features of NFSv4.1 is the introduction of stateful sessions. Sessions bring the advantages of correctness and simplicity to NFS semantics. In order to improve on the correctness of NFSv4, NFSv4.1 sessions introduce “exactly-once” semantics.

Servers maintain one or more session states in agreement with the client; they maintain the server’s state relative to the connections belonging to a client. Clients can be assured that their requests to the server have been executed, and that they will never be executed more than once.

Sessions extend the idea of NFSv4 delegations, which introduced server-initiated asynchronous callbacks; clients can initiate session requests for connections to the server. For WAN based systems, this simplifies operations through firewalls.

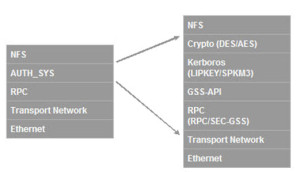

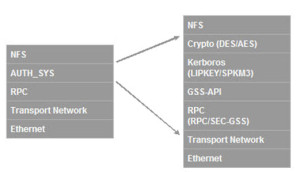

Security

An area of great confusion, many believe that NFSv4 requires the use of strong security. The NFSv4 specification simply states that implementation of strong RPC security by servers and clients is mandatory, not the use of strong RPC security. This misunderstanding may explain the reluctance of users from migrating to NFSv4 due to the additional work in implementing or modifying their existing Kerberos security.

Security is increasingly important as NFSv4 makes data more easily available over the WAN. This feature was considered so important by the IETF NFS working group that the security specification using Kerberos v5 was “retrofitted” to the NFSv2 and NFSv3 specifications.

Although access to an NFS filesystem without strong security such as provided by Kerberos is possible, across a WAN it should really be considered only as a temporary measure. In that spirit, it should be noted that NFSv4 can be used without implementing Kerberos security. The fact that it is possible does not make it desirable! A fuller description of the issues and some migration considerations can be found in the SNIA White Paper “Migrating from NFSv3 to NFSv4”.

Many of the practical issues faced in implementing robust Kerberos security in a UNIX environment can be eased by using a Windows Active Directory (AD) system. Windows uses the standard Kerberos protocol as specified in RFC 1510; AD user accounts are represented to Kerberos in the same way as accounts in UNIX realms. This can be a very attractive solution in mixed-mode environments.

In the next post, we’ll discuss one of the primary features of NFSv4.1; pNFS, or parallelized NFS, and some of the new work being done in support of NFSv4.2.

FOOTNOTE: Parts of this blog were originally published in Usenix ;login: February 2012 under the title The Background to NFSv4.1. Used with permission.

Update: Want to learn more about NFS? Check out these SNIA ESF webcasts: