More than 1,200 people have already watched our Ethernet Storage Forum (ESF) Great Storage Debate webcast “File vs. Block vs. Object Storage.” If you haven’t seen it yet, it’s available on demand. This great debate generated many interesting questions. As promised, our experts have answered them all here.

Q. What about the encryption technologies on file storage? Do they exist, and how do they affect the performance compared to unencrypted storage?

A. Yes, encryption of file data at rest can be done by the storage software, operating system, or the drives themselves (self-encrypting drives). Encryption of file data on the wire can be done by the storage software, OS, or specialized network cards. These methods can usually also be applied to block and object storage. Encryption requires processing power so if it’s done by the main CPU it might affect performance. If encryption is offloaded to the HBA, drive, or SmartNIC then it might not affect performance.

Q. Regarding block size, I thought that block size settings were also used to tune and optimize file protocol transfer, for example in NFS, am I wrong?

A. That is correct, block size refers to the size of data in each I/O and can be applied to block, file and object storage, though it may not be used very often for object storage. NFS and SMB both let you specific block I/O size.

Q. What is the main difference between object and file? Is it true that File has a hierarchical structure, while object does not?

A. Yes that is one important difference. Another difference is the access method–folder/file/offset for files and key-value for objects. File storage also often allows access to specific data within a file and in many cases shared writes to the same file, while object storage typically offers only shared reads and most object storage systems do not allow direct updates to existing objects.

Q. What is the best way to backup a local Object store system?

A. Most object storage systems have built-in data protection using either replication or erasure coding which often replicates the data to one or more remote locations. If you deploy local object storage that does not include any remote replication or erasure coding protection, you should implement some other form of backup or replication, perhaps at the hardware or operating system level.

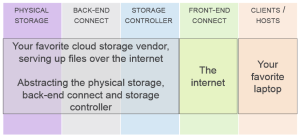

Q. I feel that this discussion conflates object storage with cloud storage features, and presumes certain cloud features (for example security) that are not universally available or really part of Object Storage. This is a very common problem with discussions of objects — they typically become descriptions of one vendor’s cloud features.

A. Cloud storage can be block, file, and/or object, though object storage is perhaps more popular in public and private cloud than it is in non-cloud environments. Security can be required and deployed in both enterprise and cloud storage environments, and for block, file and object storage. It was not the intention of this webinar to conflate cloud and object storage; we leave that to the SNIA Cloud Storage Initiative (CSI).

Q. How do open source block, file and object storage products play into the equation?

A. Open source software solutions are available for block, file and object storage. As is usually the case with other open-source, these solutions typically make storage (block, file or object) available at a lower acquisition cost than commercial storage software or appliances, but at the cost of higher complexity and higher integration/support effort by the end user. Thus customers who care most about simplicity and minimizing their integration/support work tend to buy commercial appliances or storage software, while large customers who have enough staff to do their own storage integration, testing and support may prefer open-source solutions so they don’t have to pay software license fees.

Q. How is data [0s and 1s in hard disk] converted to objects or vice versa?

A. In the beginning there were electrons, with conductors, insulators, and semi-conductors (we skipped the quantum physics level of explanation). Then there were chip companies, storage companies, and networking companies. Then The Storage Networking Industry Association (SNIA) came along… The short answer is some software (running in the storage server, storage device, or the cloud) organizes the 0s and 1s into objects stored in a file system or object store. The software makes these objects (full of 0s and 1s) available via a key-value systems and/or a RESTful API. You submit data (stream of 1s and 0s) and get a key-value in return. Or you submit a key-value and get the object (stream of 1s and 0s) in return.

Q. What is the difference (from an operating system perspective where the file/object resides) between a file in mounted NFS drive and object in, for example Google drive? Isn’t object storage (under the hood) just network file system with rest API access?

A. Correct–under the hood there are often similarities between file and object storage. Some object storage systems store the underlying data as file and some file storage systems store the underlying data as objects. However, customers and applications usually just care about the access method, performance, and reliability/availability, not the underlying storage method.

Q. I’ve heard that an Achilles’ Heel of Object is that if you lose the name/handle, then the object is essentially lost. If true, are there ways to mitigate this risk?

A. If you lose the name/handle or key-value, then you cannot access the object, but most solutions using object storage keep redundant copies of the name/handle to avoid this. In addition, many object storage systems also store metadata about each object and let you search the metadata, so if you lose the name/handle you can regain access to the object by searching the metadata.

Q. Why don’t you mention concepts like time to first byte for object storage performance?

A. Time to first byte is an important performance metric for some applications and that can be true for block, file, and object storage. When using object storage, an application that is streaming out the object (like online video streaming) or processing the object linearly from beginning to end might really care about time to first byte. But an application that needs to work on the entire object might care more about time to load/copy the entire object instead of time to first byte.

Q. Could you describe how storage supports data temperatures?

A. Data temperatures describe how often data is accessed, where “hot” data is accessed often, “warm” data occasionally, and “cold” data rarely. A storage system can tier data so the hottest data is on the fastest storage while the coldest data is on the least expensive (and presumably slowest) storage. This could mean using block storage for the hot data, file storage for the warm data, and object storage for the cold data, but that is just one option. For example, block storage could be for cold data while file storage is for hot data, or you could have three tiers of file storage.

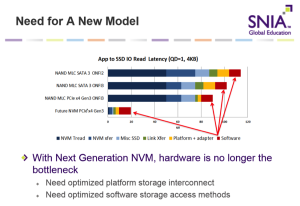

Q. Fibre channel uses SCSI. Does NVMe over Fibre Channel use SCSI too? That would diminish NVMe performance greatly.

A. NVMe over Fabrics over Fibre Channel does not use the Fibre Channel Protocol (FCP) and does not use SCSI. It runs the NVMe protocol over a FC-NVMe transport on top of the physical Fibre Channel network. In fact none of the NVMe over Fabrics options use SCSI.

Q. I get confused when some one says block size for block storage, also block size for NFS storage and object storage as well. Does block size means different for different storage type?

A. In this case “block size” refers to the size of the data access and it can apply to block, file, or object storage. You can use 4KB “block size” to access file data in 4KB chunks, even though you’re accessing it through a folder/file/offset combination instead of a logical block address. Some implementations may limit which block sizes you can use. Object storage tends to use larger block sizes (128KB, 1MB, 4MB, etc.) than block storage, but this is not required.

Q. One could argue that file system is not really a good match for big data. Would you agree?

A. It depends on the type of big data and the access patterns. Big data that consists of large SQL databases might work better on block storage if low latency is the most important criteria. Big data that consists of very large video or image files might be easiest to manage and protect on object storage. And big data for Hadoop or some machine learning applications might work best on file storage.

Q. It is my understanding that the unit for both File Storage & Object storage is File – so what is the key/fundamental difference between the two?

A. The unit for file storage is a file (folder/file/offset or directory/file/offset) and the unit for object storage is an object (key-value or object name). They are similar but not identical. For example file storage usually allows shared reads and writes to the same file, while object storage usually allows shared reads but not shared writes to the object. In fact many object storage systems do not allow any writes or updates to the middle of an object–they either allow only appends to the end of the object or don’t allow any changes to an object at all once it has been created.

Q. Why is key value store more efficient and less costly for PCIe SSD? Can you please expand?

A. If the SSD supports key-value storage directly, then the applications or storage servers don’t have to perform the key-value translation. They simply submit the key value and then write or read the related data directly from the SSDs. This reduces the cost of the servers and software that would otherwise have to manage the key-value translations, and could also increase object storage performance. (Key-value storage is not inherently more efficient for PCIe SSDs than for other types of SSDs.)

Interested in more SNIA ESF Great Storage Debates? Check out:

If you have an idea for another storage debate, let us know by commenting on this blog. Happy debating!